The Missing Piece Meets the Big O

The best children’s books, as Tolkien asserted and Sendak agreed, aren’t written for children; they are enjoyed by children, but they speak to our deepest longings and fears, and thus enchant humans of all ages. But the spell only works, as legendary children’s book editor Ursula Nordstrom memorably remarked, “if the dull adult isn’t too dull to admit that he doesn’t know the answers to everything.”

Few storytellers have immunized us against our adult dullness, generation after generation, more potently than Shel Silverstein, one of the many beloved authors and artists — alongside Maurice Sendak, E.B. White, Margaret Wise Brown, and dozens of others — whose genius Nordstrom cultivated under her compassionate and creatively uncompromising wing. In a letter from September of 1975, she wrote: “Shel promised me that it was in really good and almost final shape… I hope with all my heart that this is really the case.” Silverstein had gone to visit Nordstrom some weeks earlier and recited the story for her, which she found to be “very very good (in fact terrific).” “I hope he hasn’t messed it up,” she adds in the letter, “and I’m pretty sure he hasn’t.”Nordstrom’s intuition and her unflinching faith in her authors and artists was never misplaced.

In 1976, The Missing Piece Meets the Big O (public library) was published — a minimalist, maximally wonderful allegory at the heart of which is the emboldening message that true love doesn’t complete us, even though at first it might appear to do that, but lets us grow and helps us become more fully ourselves. It’s a story especially poignant for those of us who have ever suffered from Savior Syndrome or Victim Syndrome and sought a partner to either fix or be fixed by, the result of which is often disastrous, always disappointing, and never salvation or true love.

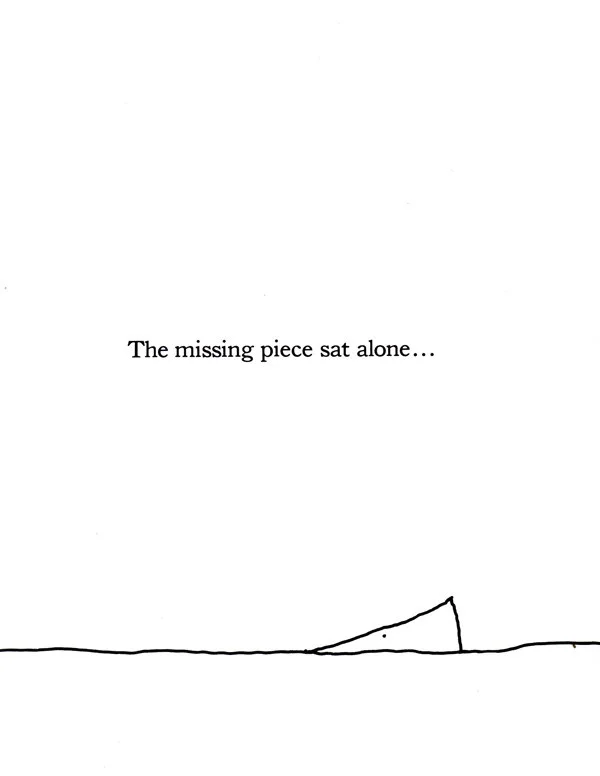

Silverstein tells the tale of a lonely little wedge that dreams of finding a big circle into which it can fit, so that together they can roll and go somewhere. Various shapes come by, but none are quite right.

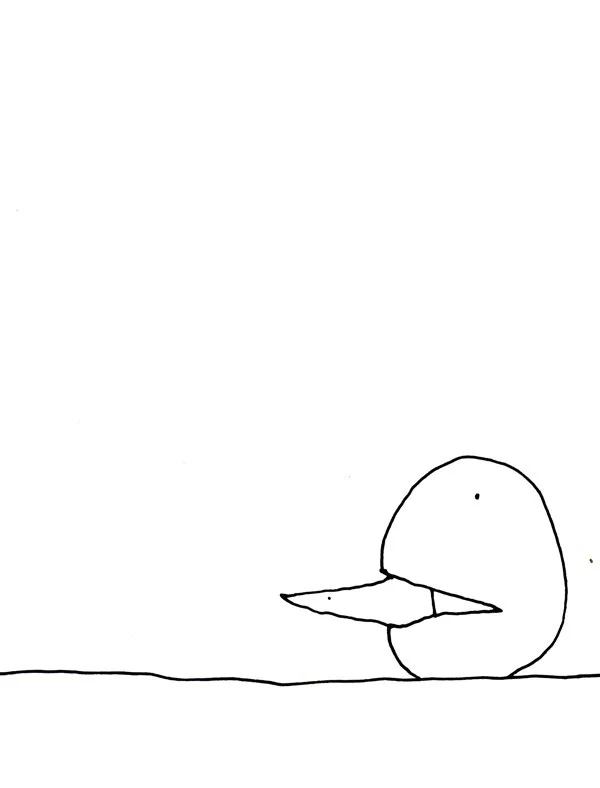

In these unbefitting rolling partners, one can’t help but recognize the archetypes implicated in failed friendships and romances — there are the damaged-beyond-repair (“some had too many pieces missing”), the overly complicated (“some had too many pieces, period”) the worshipper (“one put it on a pedestal and left it there”), the self-involved narcissist (“some rolled by without noticing”).

The missing piece tries to make itself more attractive, flashier — but that scares away the shy ones and leaves it ever lonelier.

At last, one comes along that fits just right, and the two roll on by blissfully.

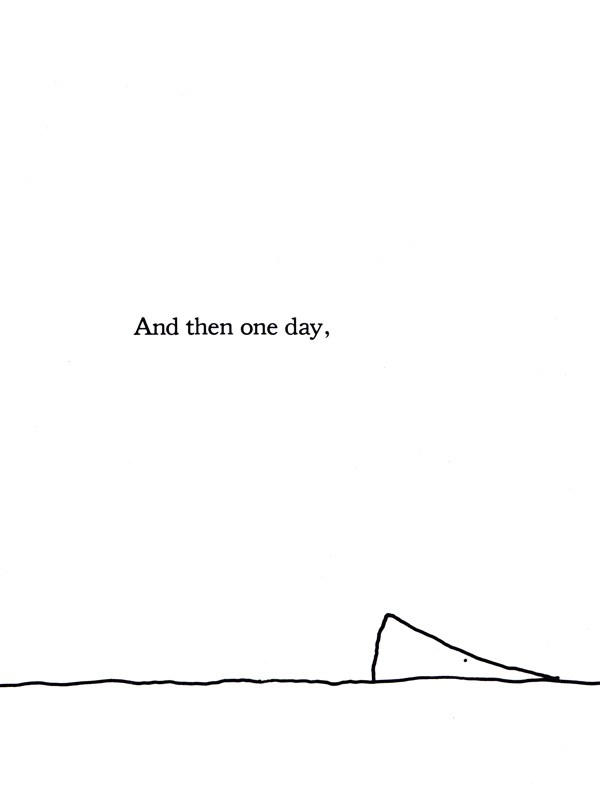

But then, something strange starts happening — the missing piece begins to grow.

And just like in any relationship where one partner grows and the other remains static, things end in disappointment — and then they just end. The static circle moves along, looking for a piece that won’t grow.

At last, a shape comes by that looks completely different — it has no piece missing at all — and introduces itself as the Big O.

The exchange between the missing piece and the Big O is nothing short of breathstopping:

“I think you are the one I have been waiting for,” said the missing piece. “Maybe I am your missing piece.”

“But I am not missing a piece,” said the Big O. “There is no place you would fit.”

“That is too bad,” said the missing piece. “I was hoping that perhaps I could roll with you…”

“You cannot roll with me,” said the Big O, “but perhaps you can roll by yourself.”

This notion is utterly revelatory for the missing piece, doubly so when the Big O asks if it has ever tried. “But I have sharp corners,” the missing piece offers half-incredulously, half-defensively. “I am not shaped for rolling.”

But corners, the Big O assures it, can wear off — another elegant metaphor for the self-refinement necessary in our personal growth. With that, the Big O rolls off, leaving the missing piece alone once more — but, this time, with an enlivening idea to contemplate.

The missing piece goes “liftpullflopliftpullflop” forward, over and over, until its edges begin to wear off and its shape starts to change. Gradually, it begins to bounce instead of bump and then roll instead of bounce — rolling, like it always dreamt of doing with the aid of another, only all by itself.

And here comes Silverstein’s tenderest, most invigorating magic — when the missing piece becomes its well-rounded self, the Big O emerges, silently and without explanation. In the final scene, the two are seen rolling side by side, calling to mind Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s contribution to history’s greatest definitions of love: “Love does not consist of gazing at each other, but in looking outward together in the same direction.”

The Missing Piece Meets the Big O is immeasurably wonderful in a way to which neither text nor pixel does any justice. Complement it with Wednesday, another minimalist and wholly wordless allegory for friendship, and Norton Juster’s vintage masterwork of poetic geometry, The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics, then treat yourself to this animated adaptation of Silverstein’s The Giving Tree and his touching duet with Johnny Cash.

By Maria Popova via BrainPickings